Moroccan Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States and the Moors

Treaty of Peace and Friendship, with additional article; also Ship-Signals Agreement. The treaty was sealed at Morocco with the seal of the Emperor of Morocco June 23, 1786 (25 Shaban, A. H. 1200), and delivered to Thomas Barclay, American Agent, June 28, 1786 (1 Ramadan, A. H. 1200). Original in Arabic. The additional article was signed and sealed at Morocco on behalf of Morocco July 15, 1786 (18 Ramadan, A. H. 1200). Original in Arabic. The Ship-Signals Agreement was signed at Morocco July 6, 1786 (9 Ramadan, A. H. 1200). Original in English.

Certified English translations of the treaty and of the additional article were incorporated in a document signed and sealed by the Ministers Plenipotentiary of the United States, Thomas Jefferson at Paris January 1, 1787, and John Adams at London January 25, 1787.

Treaty and additional article ratified by the United States July 18, 1787. As to the ratification generally, see the notes. Treaty and additional article proclaimed July 18, 1787.

Ship-Signals Agreement not specifically included in the ratification and not proclaimed; but copies ordered by Congress July 23, 1787, to be sent to the Executives of the States (Secret Journals of Congress, IV, 869; but see the notes as to this reference).

[Certified Translation of the Treaty and of the Additional Article, with Approval by Jefferson and Adams)To all Persons to whom these Presents shall come or be made known- Whereas the United States of America in Congress assembled by their Commission bearing date the twelfth day of May One thousand Seven hundred and Eighty four thought proper to constitute John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson their Ministers Plenipotentiary, giving to them or a Majority of them full Powers to confer, treat & negotiate with the Ambassador, Minister or Commissioner of His Majesty the Emperor of Morocco concerning a Treaty of Amity and Commerce, to make & receive propositions for such Treaty and to conclude and sign the same, transmitting it to the United States in Congress assembled for their final Ratification, And by one other (commission bearing date the Eleventh day of March One thousand Seven hundred & Eighty five did further empower the said Ministers Plenipotentiary or a majority of them, by writing under the* hands and Seals to appoint such Agent in the said Business as they might think proper with Authority under the directions and Instructions of the said Ministers to commence & prosecute the said Negotiations & Conferences for the said Treaty provided that the said Treaty should be signed by the said Ministers: And Whereas, We the said John Adams & Thomas Jefferson two of the said Ministers Plenipotentiary (the said Benjamin Franklin being absent) by writing under the Hand and Seal of the said John Adams at London October the fifth, One thousand Seven hundred and Eighty five, & of the said Thomas Jefferson at Paris October the Eleventh of the same Year, did appoint Thomas Barclay, Agent in the Business aforesaid, giving him the Powers therein, which by the said second Commission we were authorized to give, and the said Thomas Barclay in pursuance thereof, hath arranged Articles for a Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the United States of America and His Majesty the Emperor of Morocco, which Articles written in the Arabic Language, confirmed by His said Majesty the Emperor of Morocco & seal’d with His Royal Seal, being translated into the Language of the said United States of America, together with the Attestations thereto annexed are in the following Words, To Wit.

In the name of Almighty God,

This is a Treaty of Peace and Friendship established between us and the United States of America, which is confirmed, and which we have ordered to be written in this Book and sealed with our Royal Seal at our Court of Morocco on the twenty fifth day of the blessed Month of Shaban, in the Year One thousand two hundred, trusting in God it will remain permanent.

1. We declare that both Parties have agreed that this Treaty consisting of twenty five Articles shall be inserted in this Book and delivered to the Honorable Thomas Barclay, the Agent of the United States now at our Court, with whose Approbation it has been made and who is duly authorized on their Part, to treat with us concerning all the Matters contained therein.

2. If either of the Parties shall be at War with any Nation whatever, the other Party shall not take a Commission from the Enemy nor fight under their Colors.

3. If either of the Parties shall be at War with any Nation whatever and take a Prize belonging to that Nation, and there shall be found on board Subjects or Effects belonging to either of the Parties, the Subjects shall be set at Liberty and the Effects returned to the Owners. And if any Goods belonging to any Nation, with whom either of the Parties shall be at War, shall be loaded on Vessels belonging to the other Party, they shall pass free and unmolested without any attempt being made to take or detain them.

4. A Signal or Pass shall be given to all Vessels belonging to both Parties, by which they are to be known when they meet at Sea, and if the Commander of a Ship of War of either Party shall have other Ships under his Convoy, the Declaration of the Commander shall alone be sufficient to exempt any of them from examination.

5. If either of the Parties shall be at War, and shall meet a Vessel at Sea, belonging to the other, it is agreed that if an examination is to be made, it shall be done by sending a Boat with two or three Men only, and if any Gun shall be Bred and injury done without Reason, the offending Party shall make good all damages.

6. If any Moor shall bring Citizens of the United States or their Effects to His Majesty, the Citizens shall immediately be set at Liberty and the Effects restored, and in like Manner, if any Moor not a Subject of these Dominions shall make Prize of any of the Citizens of America or their Effects and bring them into any of the Ports of His Majesty, they shall be immediately released, as they will then be considered as under His Majesty’s Protection.

7. If any Vessel of either Party shall put into a Port of the other and have occasion for Provisions or other Supplies, they shall be furnished without any interruption or molestation.

If any Vessel of the United States shall meet with a Disaster at Sea and put into one of our Ports to repair, she shall be at Liberty to land and reload her cargo, without paying any Duty whatever.

8. If any Vessel of the United States shall be cast on Shore on any Part of our Coasts, she shall remain at the disposition of the Owners and no one shall attempt going near her without their Approbation, as she is then considered particularly under our Protection; and if any Vessel of the United States shall be forced to put into our Ports, by Stress of weather or otherwise, she shall not be compelled to land her Cargo, but shall remain in tranquillity untill the Commander shall think proper to proceed on his Voyage.

9. If any Vessel of either of the Parties shall have an engagement with a Vessel belonging to any of the Christian Powers within gunshot of the Forts of the other, the Vessel so engaged shall be defended and protected as much as possible untill she is in safety; And if any American Vessel shall be cast on shore on the Coast of Wadnoon (1) or any coast thereabout, the People belonging to her shall be protected, and assisted untill by the help of God, they shall be sent to their Country.

10. If we shall be at War with any Christian Power and any of our Vessels sail from the Ports of the United States, no Vessel belonging to the enemy shall follow untill twenty four hours after the Departure of our Vessels; and the same Regulation shall be observed towards the American Vessels sailing from our Ports.-be their enemies Moors or Christians.

11. If any Ship of War belonging to the United States shall put into any of our Ports, she shall not be examined on any Pretence whatever, even though she should have fugitive Slaves on Board, nor shall the Governor or Commander of the Place compel them to be brought on Shore on any pretext, nor require any payment for them.

12. If a Ship of War of either Party shall put into a Port of the other and salute, it shall be returned from the Fort, with an equal Number of Guns, not with more or less.

13. The Commerce with the United States shall be on the same footing as is the Commerce with Spain or as that with the most favored Nation for the time being and their Citizens shall be respected and esteemed and have full Liberty to pass and repass our Country and Sea Ports whenever they please without interruption.

14. Merchants of both Countries shall employ only such interpreters, & such other Persons to assist them in their Business, as they shall think proper. No Commander of a Vessel shall transport his Cargo on board another Vessel, he shall not be detained in Port, longer than he may think proper, and all persons employed in loading or unloading Goods or in any other Labor whatever, shall be paid at the Customary rates, not more and not less.

15. In case of a War between the Parties, the Prisoners are not to be made Slaves, but to be exchanged one for another, Captain for Captain, Officer for Officer and one private Man for another; and if there shall prove a deficiency on either side, it shall be made up by the payment of one hundred Mexican Dollars for each Person wanting; And it is agreed that all Prisoners shall be exchanged in twelve Months from the Time of their being taken, and that this exchange may be effected by a Merchant or any other Person authorized by either of the Parties.

16. Merchants shall not be compelled to buy or Sell any kind of Goods but such as they shall think proper; and may buy and sell all sorts of Merchandise but such as are prohibited to the other Christian Nations.

17. All goods shall be weighed and examined before they are sent on board, and to avoid all detention of Vessels, no examination shall afterwards be made, unless it shall first be proved, that contraband Goods have been sent on board, in which Case the Persons who took the contraband Goods on board shall be punished according to the Usage and Custom of the Country and no other Person whatever shall be injured, nor shall the Ship or Cargo incur any Penalty or damage whatever.

18. No vessel shall be detained in Port on any presence whatever, nor be obliged to take on board any Article without the consent of the Commander, who shall be at full Liberty to agree for the Freight of any Goods he takes on board.

19. If any of the Citizens of the United States, or any Persons under their Protection, shall have any disputes with each other, the Consul shall decide between the Parties and whenever the Consul shall require any Aid or Assistance from our Government to enforce his decisions it shall be immediately granted to him.

20. If a Citizen of the United States should kill or wound a Moor, or on the contrary if a Moor shall kill or wound a Citizen of the United States, the Law of the Country shall take place and equal Justice shall be rendered, the Consul assisting at the Tryal, and if any Delinquent shall make his escape, the Consul shall not be answerable for him in any manner whatever.

21. If an American Citizen shall die in our Country and no Will shall appear, the Consul shall take possession of his Effects, and if there shall be no Consul, the Effects shall be deposited in the hands of some Person worthy of Trust, untill the Party shall appear who has a Right to demand them, but if the Heir to the Person deceased be present, the Property shall be delivered to him without interruption; and if a Will shall appear, the Property shall descend agreeable to that Will, as soon as the Consul shall declare the Validity thereof.

22. The Consuls of the United States of America shall reside in any Sea Port of our Dominions that they shall think proper; And they shall be respected and enjoy all the Privileges which the Consuls of any other Nation enjoy, and if any of the Citizens of the United States shall contract any Debts or engagements, the Consul shall not be in any Manner accountable for them, unless he shall have given a Promise in writing for the payment or fulfilling thereof, without which promise in Writing no Application to him for any redress shall be made.

23. If any differences shall arise by either Party infringing on any of the Articles of this Treaty, Peace and Harmony shall remain notwithstanding in the fullest force, untill a friendly Application shall be made for an Arrangement, and untill that Application shall be rejected, no appeal shall be made to Arms. And if a War shall break out between the Parties, Nine Months shall be granted to all the Subjects of both Parties, to dispose of their Effects and retire with their Property. And it is further declared that whatever indulgences in Trade or otherwise shall be granted to any of the Christian Powers, the Citizens of the United States shall be equally entitled to them.

24. This Treaty shall continue in full Force, with the help of God for Fifty Years.

We have delivered this Book into the Hands of the before-mentioned Thomas Barclay on the first day of the blessed Month of Ramadan, in the Year One thousand two hundred.

I certify that the annex’d is a true Copy of the Translation made by Issac Cardoza Nunez, Interpreter at Morocco, of the treaty between the Emperor of Morocco and the United States of America.

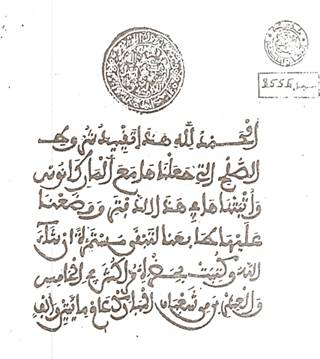

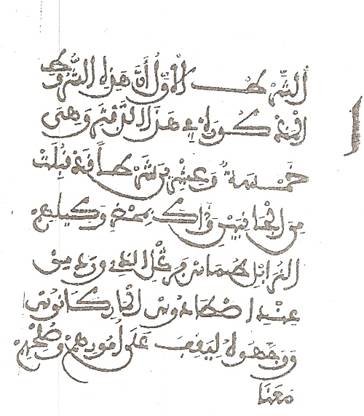

Treaty of Peace and Friendship in Arabic

Morocco is one of the first countries to recognize the independence of the United States as the Sultan Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdullah issued a declaration in 1777 allowing American ships access to Moroccan ports. In 1787 a Treaty of peace and friendship was signed in Marrakech and ratified in 1836. It is still in force making it the longest unbroken treaty in the U.S history.

The U.S had also its first consulate in Tangier in 1797 in a building given by the sultan Moulay Sliman. It is the oldest U.S diplomatic property in the world.

Below is the Treaty called the “Marrakech Treaty” in its original form as was written in 1786.

“This is a Treaty of Peace and Friendship established between Morocco and the United States of America, which is confirmed, and which we have ordered to be written in this Book and sealed with our Royal Seal at our Court of Morocco on the twenty fifth day of the blessed Month of Shaban, in the Year One thousand two hundred, trusting in God it will remain permanent” The Sultan Mohammed Ben Abdullah.

2. If one of the Parties shall be at War with any Nation whatsoever, the other Party shall not take a Commission either from the Enemy nor fight under their Colors.

3. If either of the Parties shall be at War with any Nation whatever and take a Prize belonging to that Nation, and there shall be found on board Subjects or Effects belonging to of the Parties, the Subjects shall be set at Liberty and the Effects returned to the Owners. In addition, if any Goods belonging to any Nation, with whom either of the Parties shall be at War, shall be loaded on Vessels belonging to the other Party, they shall pass free and unmolested without any attempt being made to take or detain them.

One of the hard facts of life is that the United States of America is not a Christian Nation. The following Treaty was made by the United States of America with the Barbary Pirates. It passed the 5th Congress without a hitch. Article 11 was made part of the record to convince the Muslims that the United States of America is not a Christian Nation, and therefore peace could be established between the two nations.

INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS

OF THE

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

1776-1949

Compiled under the direction of

CHARLES I. BEVANS, LL.B.

Assistant Legal Adviser, Department of State

Volume II

PHILIPPINES-

UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC

DEPARTMENT OF STATE PUBLICATION 8728

Released February 1974

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C. 20402 – Price $14.35

pages 1070 – 1074

Tripoli

PEACE AND FRIENDSHIP

Treaty signed at Tripoli November 4, 1796, and at Algiers January 3, 1797

Senate advice and consent to ratification June 7, 1797

Ratified by the President of the United States June 10, 1797

Entered into force June 10, 1797

Proclaimed by the President of the United States June 10, 1797

Superseded April 17, 1806, by treaty of June, 4, 18051

8 Stat. 154; Treaty Series 3582

TREATY OF PEACE AND FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE BEY AND SUBJECTS OF TRIPOLI OF BARBARY

ARTICLE 1

There is a firm and perpetual Peace and friendship between the United States of America and the Bey and subjects of Tripoli of Barbary, made by the free consent of both parties, and guaranteed by the most potent Dey & regency of Algiers.

ARTICLE 2

If any goods belonging to any nation with which either of the parties is at war shall be loaded on board of vessels belonging to the other party they shall pass free, and no attempt shall be made to take or detain them.

ARTICLE 3

If any citizens, subjects or effects belonging to either party shall be found on board a prize vessel taken from an enemy by the other party, such citizens or subjects shall be set at liberty, and the effects restored to the owners.

ARTICLE 4

Proper passports are to be given to all vessels of both parties, by which they are to be known. And, considering the distance between the two countries, eighteen months from the date of this treaty shall be allowed for procuring such passports. During this interval the other papers belonging to such vessels shall be sufficient for their protection.

ARTICLE 5

A citizen or subject of either party having bought a prize vessel condemned by the other party or by any other nation, the certificate of condemnation and bill of sale shall be a sufficient passport for such vessel for one year; this being a reasonable time for her to procure a proper passport.

ARTICLE 6

Vessels of either party putting into the ports of the other and having need of provisions or other supplies, they shall be furnished at the market price. And if any such vessel shall so put in from a disaster at sea and have occasion to repair, she shall be at liberty to land and reembark her cargo without paying any duties. But in no case shall she be compelled to land her cargo.

ARTICLE 7

Should a vessel of either party be cast on the shore of the other, all proper assistance shall be given to her and her people; no pillage shall be allowed; the property shall remain at the disposition of the owners, and the crew protected and succoured till they can be sent to their country.

ARTICLE 8

If a vessel of either party should be attacked by an enemy within gun-shot of the forts of the other she shall be defended as much as possible. If she be in port she shall not be seized or attacked when it is in the power of the other party to protect her. And when she proceeds to sea no enemy shall be allowed to pursue her from the same port within twenty four hours after her departure.

ARTICLE 9

The commerce between the United States and Tripoli, – the protection to be given to merchants, masters of vessels and seamen, – the reciprocal right of establishing consuls in each country, and the privileges, immunities and jurisdictions to be enjoyed by such consuls, are declared to be on the same footing with those of the most favoured nations respectively.

ARTICLE 10

The money and presents demanded by the Bey of Tripoli as a full and satisfactory consideration on his part and on the part of his subjects for this treaty of perpetual peace and friendship are acknowledged to have been received by him previous to his signing the same, according to a receipt which is hereto annexed, except such part as is promised on the part of the United States to be delivered and paid by them on the arrival of their Consul in Tripoli, of which part a note is likewise hereto annexed. And no pretence of any periodical tribute or farther payment is ever to be made by either party.

ARTICLE 11

As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion,4 – as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen, – and as the said States never have entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mehomitan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.

ARTICLE 12

In case of any dispute arising from a violation of any of the articles of this treaty no appeal shall be made to arms, nor shall war be declared on any pretext whatever. But if the Consul residing at the place where the dispute shall happen shall not be able to settle the same, an amicable reference shall be made to the mutual friend of the parties, the Dey of Algiers, the parties hereby engaging to abide by his decision. And he by virtue of his signature to this treaty engages for himself and successors to declare the justice of the case according to the true interpretation of the treaty, and to use all the means in his power to enforce the observance of the same.

Signed and sealed at Tripoli of Barbary the 3d day of Jumad in the year of the Higera 1211 – corresponding with the 4th day of Novr 1796 by

JUSSUF BASHAW MAHOMET Bey SOLIMAN Kaya

MAMET – Treasurer GALIL – Genl of the Troops

AMET – Minister of Marine MAHOMET – Comt of the city

AMET – Chamberlain MAMET – Secretary

ALLY – Chief of the Divan

Signed and sealed at Algiers the 4th day of Argib 1211 – corresponding with the 3d day of January 1797 by HASSAN BASHAW Dey

and by the Agent plenipotentiary of the United States of America JOEL BARLOW [SEAL]

[THE “RECEIPT”]

Praise be to God & c-

The present writing done by our hand and delivered to the American Captain OBrien makes known that he has delivered to us forty thousand Spanish dollars, – thirteen watches of gold, silver & pins-back, – five rings, of which three of diamonds, one of saphire and one with a watch in it, – one hundred & forty piques of cloth, and four caftans of brocade, – and these on account of the peace concluded with the Americans.

Given at Tripoli in Barbary the 20th day of Jumad 1211, corresponding with the 21st day of Novr 1796 –

JUSSUF BASHAW – Bey

whom God Exalt

The foregoing is a true copy of the receipt given by Jussuf Bashaw – Bey of Tripoli –

HASSAN BASHAW – Dey of Algiers

The foregoing is a literal translation of the writing in Arabic on the opposite page

JOEL BARLOW

On the arrival of a consul of the United States in Tripoli he is to deliver to Jussuf Bashaw Bey –

twelve thousand Spanish dollars

five hawsers – 8 Inch

three cables – 10 Inch

twenty five barrels tar

twenty five do pitch

ten do rosin

five hundred pine boards

five hundred oak do

ten masts (without any measure mentioned, suppose for vessels from 2 to 300 ton)

twelve yards

fifty bolts canvas

four anchors

And these when delivered are to be in full of all demands on his part or on that of his successors from the United States according as it is expressed in the tenth article of the following treaty. And no farther demand of tributes, presents or payments shall ever be made.

Translated from the Arabic on the opposite page, which is signed & sealed by Hassan Bashaw Dey of Algiers – the 4th day of Argib 1211 – or the 3d day of Jany 1797 – by –

JOEL BARLOW

[APPROVAL OF U.S. MINISTER AT LISBON]To all to whom these Presents shall come or be made known.

Whereas the Underwritten David Humphreys hath been duly appointed Commissioner Plenipotentiary by Letters Patent, under the Signature of the President and Seal of the United States of America, dated the 30th of March 1795, for negociating and concluding a Treaty of Peace with the Most Illustrious the Bashaw, Lords and Governors of the City & Kingdom of Tripoli; whereas by a Writing under his Hand and Seal dated the 10th of February 1796, he did (in conformity to the authority committed to me therefor) constitute and appoint Joel Barlow and Joseph Donaldson Junior Agents jointly and seperately in the business aforesaid; whereas the annexed Treaty of Peace and Friendship was agreed upon, signed and sealed at Tripoli of Barbary on the 4th of November 1796, in virtue of the Powers aforesaid and guaranteed by the Most potent Dey and Regency of Algiers; and whereas the same was certified at Algiers on the 3d of January 1797, with the Signature and Seal of Hassan Bashaw Dey, and of Joel Barlow one of the Agents aforesaid, in the absence of the other.

Now Know ye, that I David Humphreys Commissioner Plenipotentiary aforesaid, do approve and conclude the said Treaty, and every article and clause therein contained, reserving the same nevertheless for the final Ratification of the President of the United States of America, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate of the said United States.

In testimony whereof I have signed the same with my Name and Seal, at the City of Lisbon this 10th of February 1797.

DAVID HUMPHREYS [SEAL] [United States Minister at Lisbon]

1 TS 359, post, p. 1081.

2 For a detailed study of this treaty, see 2 Miller 349.

3 This translation from the Arabic by Joel Barlow, Consul General at Algiers, has been printed in all official and unofficial treaty collections since it first appeared in 1797 in the Session Laws of the Fifth Congress, first session. In a “Note Regarding the Barlow Translation” Hunter Miller stated: “. . . Most extraordinary (and wholly unexplained) is the fact that Article 11 of the Barlow translation, with its famous phrase, ‘the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion.’ does not exist at all. There is no Article 11. The Arabic text which is between Articles 10 and 12 is in form a letter, crude and flamboyant and withal quite unimportant, from the Dey of Algiers to the Pasha of Tripoli. How that script came to be written and to be regarded, as in the Barlow translation, as Article 11 of the treaty as there written, is a mystery and seemingly must remain so. Nothing in the diplomatic correspondence of the time throws any light whatever on the point.” (2 Miller 384.)

The Miller edition also contains an annotated translation from the original Arabic made in 1930 by Dr. C. Snouck Hurgronje of Leiden; for text, see p. 1075.

4 See footnote 3, p. 1070.

MANY OF YOU NEVER KNOWN THE RELATIONSHIP WITH THE MOORISH EMPIRE. THE SCHOOLS and ISLAMIC MOVEMENTS HAVE KEPT THIS A SECRET.

Office of the Historian – U.S. Department of State

Morocco and the United States have a long history of friendly relations. This North African nation was one of the first states to seek diplomatic relations with America. In 1777, Sultan Sidi Muhammad Ben Abdullah, the most progressive of the Barbary leaders who ruled Morocco from 1757 to 1790, announced his desire for friendship with the United States. The Sultan’s overture was part of a new policy he was implementing as a result of his recognition of the need to establish peaceful relations with the Christian powers and his desire to establish trade as a basic source of revenue. Faced with serious economic and political difficulties, he was searching for a new method of governing which required changes in his economy. Instead of relying on a standing professional army to collect taxes and enforce his authority, he wanted to establish state-controlled maritime trade as a new, more reliable, and regular source of income which would free him from dependency on the services of the standing army. The opening of his ports to America and other states was part of that new policy.

The Sultan issued a declaration on December 20, 1777, announcing that all vessels sailing under the American flag could freely enter Moroccan ports. The Sultan stated that orders had been given to his corsairs to let the ship “des Americains” and those of other European states with which Morocco had no treaties-Russia Malta, Sardinia, Prussia, Naples, Hungary, Leghorn, Genoa, and Germany-pass freely into Moroccan ports. There they could “take refreshments” and provisions and enjoy the same privileges as other nations that had treaties with Morocco. This action, under the diplomatic practice of Morocco at the end of the 18th century, put the United States on an equal footing with all other nations with which the Sultan had treaties. By issuing this declaration, Morocco became one of the first states to acknowledge publicly the independence of the American Republic.

On February 2O, l778, the sultan of Morocco reissued his December 20, 1777, declaration. American officials, however, only belatedly learned of the Sultan’s full intentions. Nearly identical to the first, the February 20 declaration was again sent to all consuls and merchants in the ports of Tangier, Sale, and Mogador informing them the Sultan had opened his ports to Americans and nine other European States. Information about the Sultan’s desire for friendly relations with the United States first reached Benjamin Franklin, one of the American commissioners in Paris, sometime in late April or early May 1778 from Etienne d’Audibert Caille, a French merchant of Sale. Appointed by the Sultan to serve as Consul for all the nations unrepresented in Morocco, Caille wrote on behalf of the Sultan to Franklin from Cadiz on April 14, 1778, offering to negotiate a treaty between Morocco and the United States on the same terms the Sultan had negotiated with other powers. When he did not receive a reply, Caille wrote Franklin a second letter sometime later that year or in early 1779. When Franklin wrote to the committee on Foreign Affairs in May 1779, he reported he had received two letters from a Frenchman who “offered to act as our Minister with the Emperor” and informed the American commissioner that “His Imperial Majesty wondered why we had never sent to thank him for being the first power on this side of the Atlantic that had acknowledged our independence and opened his ports to us.” Franklin, who did not mention the dates of Caille’s letters or when he had received them, added that he had ignored these letters because the French advised him that Caille was reputed to be untrustworthy. Franklin stated that the French King was willing to use his good offices with the Sultan whenever Congress desired a treaty and concluded, “whenever a treaty with the Emperor is intended, I suppose some of our naval stores will be an acceptable present and the expectation of continued supplies of such stores a powerful motive for entering into and continuing a friendship.”

Since the Sultan received no acknowledgement of his good will gestures by the fall of 1 779, he made another attempt to contact the new American government. Under instructions from the Moroccan ruler, Caille wrote a letter to Congress in September 1779 in care of Franklin in Paris to announce his appointment as Consul and the Sultan’s desire to be at peace with the United States. The Sultan, he reiterated, wished to conclude a treaty “similar to those Which the principal maritime powers have with him.” Americans were invited to “come and traffic freely in these ports in like manner as they formerly did under the English flag.” Caille also wrote to John Jay, the American representative at Madrid, on April 21,1780, asking for help in conveying the Sultan’s message to Congress and enclosing a copy of Caille’s commission from the Sultan to act as Consul for all nations that had none in Morocco, as well as a copy of the February 20, 1778, declaration. Jay received that letter with enclosures in May 1780, but because it was not deemed to be of great importance, he did not forward it and its enclosures to Congress until November 30, 1 780.

Before Jay’s letter with the enclosures from Caille reached Congress, Samuel Huntington, President of Congress, made the first official response to the Moroccan overtures in a letter of November 28,1780, to Franklin. Huntington wrote that Congress had received a letter from Caille, and asked Franklin to reply. Assure him, wrote Huntington, “in the name of Congress and in terms most respectful to the Emperor that we entertain a sincere disposition to cultivate the most perfect friendship with him, and are desirous to enter into a treaty of commerce with him; and that we shall embrace a favorable opportunity to announce our wishes in form.”

The U.S. Government sent its first official communication to the Sultan of Morocco in December 1780. It read:

We the Congress of the 13 United States of North America, have been informed of your Majesty’s favorable regard to the interests of the people we represent, which has been communicated by Monsieur Etienne d’Audibert Caille of Sale, Consul of Foreign nations unrepresented in your Majesty’s states. We assure you of our earnest desire to cultivate a sincere and firm peace and friendship with your Majesty and to make it lasting to all posterity. Should any of the subjects of our states come within the ports of your Majesty’s territories, we flatter ourselves they will receive the benefit of your protection and benevolence. You may assure yourself of every protection and assistance to your subjects from the people of these states whenever and wherever they may have it in their power. We pray your Majesty may enjoy long life and uninterrupted prosperity.

No action was taken either by Congress or the Sultan for over 2 years. The Americans, preoccupied with the war against Great Britain, directed their diplomacy at securing arms, money, military support, and recognition from France, Spain, and the Netherlands and eventually sought peace with England. Moreover, Sultan Sidi Muhammad and more pressing concerns and focused on his relations with the European powers, especially Spain and Britain over the question of Gibraltar. From 1778 to 1782, the Moroccan leader also turned to domestic difficulties resulting from drought and famine, and unpopular food tax, food shortages and inflation of food prices, trade problems, and a disgruntled military.

The American commissioners in Paris, John Adams, Jay, and Franklin urged Congress in September 1783 to take some action in negotiating a treaty with Morocco. “The Emperor of Morocco has manifested a very friendly disposition towards us,” they wrote. “He expects and is reading to receive a Minister from us; and as he may be succeeded by a prince differently disposed, a treaty with him may be of importance. Our trade to the Mediterranean will not be inconsiderable, and the friendship of Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli may become very interesting in case the Russians should succeed in their endeavors to navigate freely into it by Constantinople.”

Congress finally acted in the spring of 1784. On May 7, Congress authorized its Ministers in Paris, Franklin, Jay, and Adams, to conclude treaties of amity and commerce with Russia, Austria, Prussia, Denmark, Saxony, Hamburg, great Britain, Spain, Portugal, Genoa, Tuscany, Rome, Naples, Venice, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Porte as well as the Barbary States of Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. The treaties with the Barbary States were to be in force for 10 years or longer. The commissioners were instructed to inform the Sultan of Morocco of the “great satisfaction which Congress feels from the amicable disposition he has shown towards these states.” They were asked to state that “the occupations of the war and distance of our situation have prevented our meeting his friendship so early as we wished.” A few days later, commissions were given to the three men to negotiate the treaties.

Continued delays by American officials exasperated the sultan and prompted him to take more drastic action to gain their attention. On October 11,1784, the Moroccans captured the American merchant ship, Betsey. After the ship and crew were taken to Tangier, he announced that he would release the men, ship, and cargo once a treaty with the United States was concluded. Accordingly, preparation for negotiations with Morocco began in 1785. On March 1 Congress authorized the commissioners to delegate to some suitable agent the authority to negotiate treaties with the Barbary States. The agent was required to follow the commissioners’ instructions and to submit the negotiated treaty to them for approval. Congress also empowered the commissioners to spend a maximum of 80,000 dollars to conclude treaties with these states. Franklin left Paris on July 12, 1785, to return to the United States, 3 days after the Sultan released the Betsey and its crew. Thomas Jefferson became Minister to France and thereafter negotiations were conducted by Adams in London and Jefferson in Paris. On October 11, 1785, the commissioners appointed Thomas Barclay, American Consul in Paris, to negotiate a treaty with Morocco on the basis of a draft treaty drawn up by the commissioners. That same day the commissioners appointed Thomas Lamb as special agent to negotiate a treaty with Algiers. Barclay was given a maximum of 20,000 dollars for the treaty and instructed to gather information concerning the commerce, ports, naval and land forces, languages, religion, and government as well as evidence of Europeans attempting to obstruct American negotiations with the Barbary States.

Barclay left Paris on January 15, 1 786, and after several stops, including 21/2 months in Madrid, arrived in Marrakech on June 19. While the French offered some moral support to the United States in their negotiations with Morocco, it was the Spanish government that furnished substantial backing in the form of letters from the Spanish King and Prime Minister to the Sultan of Morocco. After a cordial welcome, Barclay conducted the treaty negotiations in two audiences with Sidi Muhammad and Tahir Fannish, a leading Moroccan diplomat from a Morisco family in Sale who headed the negotiations. The earlier proposals drawn up by the American commissioners in Paris became the basis for the treaty. While the Emperor opposed several articles, the final form contained in substance all that the Americans requested. When asked about tribute, Barclay stated that he “had to offer to His Majesty the friendship of the United States and to receive his in return, to form a treaty with him on liberal and equal terms. But if any engagements for future presents or tributes were necessary, I must return without any treaty.” The Moroccan leader accepted Barclay’s declaration that the United States would offer friendship but no tribute for the treaty, and the question of presents or tribute was not raised again. Barclay accepted no favor except the ruler’s promise to send letters to Constantinople, Tunisia, Tripoli, and Algiers recommending they conclude treaties with the United States.

Barclay and the Moroccans quickly reached agreement on the Treaty of Friendship and Amity. Also called the Treaty of Marrakech, it was sealed by the Emperor on June 23 and delivered to Barclay to sign on June 28. In addition, a separate ship seals agreement, providing for the identification at sea of American and Moroccan vessels, was signed at Marrakech on July 6,1786. Binding for 50 years, the Treaty was signed by Thomas Jefferson at Paris on January 1, 1787, and John Adams at London on January 25, 1787, and was ratified by Congress on July 18, 1787. The negotiation of this treaty marked the beginning of diplomatic relations between the two countries and it was the first treaty between any Arab, Muslim, or African State and the United States.

Congress found the treaty with Morocco highly satisfactory and passed a note of thanks to Barclay and to Spain for help in the negotiations. Barclay had reported fully on the amicable negotiations and written that the king of Morocco had “acted in a manner most gracious and condescending, and I really believe the Americans possess as much of his respect and regard as does any Christian nation whatsoever.” Barclay portrayed the King as “a just man, according to this idea of justice, of great personal courage, liberal to a degree, a lover of his people, stern” and “rigid in distributing justice.” The Sultan sent a friendly letter to the President of Congress with the treaty and included another from the Moorish minister, Sidi Fennish, which was highly complimentary of Barclay.

The United States established a consulate in Morocco in 1797. President Washington had requested funds for this post in a message to Congress on March 2, 1795, and James Simpson, the U.S. Consul at Gibraltar who was appointed to this post, took up residence in Tangier 2 years later. Sultan Sidi Muhammad’s successor, Sultan Moulay Soliman, had recommended to Simpson the establishment of a consulate because he believed it would provide greater protection for American vessels. In 1821, the Moroccan leader gave the United States one of the most beautiful buildings in Tangier for its consular representative. This building served as the seat of the principal U.S. representative to Morocco until 1956 and is the oldest piece of property owned by the United States abroad.

U. S.-Moroccan relations from 1777 to 1787 reflected the international and economic concerns of these two states in the late 18th century. The American leaders and the Sultan signed the 1786 treaty, largely for economic reasons, but also realized that a peaceful relationship would aid them in their relations with other powers. The persistent friendliness of Sultan Sidi Muhammad to the young republic, in spite of the fact that his overtures were initially ignored, was the most important factor in the establishment of this relationship.

THIS IS LEGAL RECORD FOR YOU TO KNOW THAT EVEN THE DEY DECLARED WAR WITH THE UNION. AS C.M. Bey says, Here is my legal proof.

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE January 24, 1996

the problem he noted: ‘‘Considering that Congress alone is constitutionally invested with the power of changing our condition from peace to war, I have thought it my duty to await their authority for using force in any degree which could be avoided.’’

1 Richardson 377. Military conflicts in the Mediterranean continued after Jefferson left office. The Dey of Algiers made war against U.S. citizens trading in that region and kept some in captivity. With the conclusion of the War of 1812 with England, President Madison recommended to Congress in 1815 that it declare war on Algiers: ‘‘I recommend to Congress the expediency of an act declaring the existence of a state of war between the United States and the Dey and Regency of Algiers, and of such provisions as may be requisite for a vigorous prosecution of it to a successful issue.’’

2 Richardson 539. Instead of a declaration of war, Congress passed legislation ‘‘for the protection of the commerce of the United States against the Algerine cruisers.’’ The first line of the statute read: ‘‘Whereas the Dey of Algiers, on the coast of Barbary, has commenced a predatory warfare against the United States. . . .’’ Congress gave Madison authority to use armed vessels for the purpose of protecting the commerce of U.S.seamen on the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and adjoining seas. U.S. vessels (both governmental and private) could ‘‘subdue, seize, and make prize of all vessels, goods and effects of or belonging to the Dey of Algiers.’’ 3 Stat. 230 (1815). An American flotilla set sail for Algiers, where it captured two of the Dey’s ships and forced him to stop the piracy, release all captives, and renounce the practice of annual tribute payments. Similar treaties were obtained from Tunis and Tripoli. By the end of 1815, Madison could report to Congress on the successful termination of the war with Algiers.

LEGISLATIVE CONTROLS ON PROSPECTIVE ACTIONS

Can Congress only authorize and declare war, or may it also establish limits on prospective presidential actions? The statutes authorizing President Washington to ‘‘protect the inhabitants’’ of the frontiers ‘‘from hostile incursions of the Indians’’ were interpreted by the Washington administration as authority for defensive, not offensive, actions.

1 Stat. 96, § 5 (1789); 1 Stat. 121, § 16 (1790); 1 Stat. 222 (1791). Secretary of War Henry Knox wrote to Governor Blount on October 9, 1792: ‘‘The Congress which possess the powers of declaring War will assemble on the 5th of next Month—Until their judgments shall be made known it seems essential to confine all your operations to defensive measures.’’ 4 The Territorial Papers of the United States 196 (Clarence Edwin Carter ed. 1936). President Washington consistently held to this policy. Writing in 1793, he said that any offensive operations against the Creek Nation must await congressional action: ‘‘The Constitution vests the power of declaring war with Congress; therefore no offensive expedition of importance can be undertaken until after they have deliberated upon the subject, and authorized such a measure.’’ 33 The Writings of George Washington 73. The statute in 1792, upon which President Washington relied for his actions in the Whiskey Rebellion, conditioned the use of military force by the President upon an unusual judicial check. The legislation said that whenever the United States ‘‘shall be invaded, or be in imminent danger of invasion from any foreign nation or Indian tribe,’’ the President may call forth the state militias to repel such invasions and to suppress insurrections.’’ 1 Stat. 264, § 1 (1792). However, whenever federal laws were opposed and their execution obstructed in any state, ‘‘by combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings, or by the powers vested in the marshals by this act,’’ the President would have to be first notified of that fact by an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court or by a federal district judge. Only after that notice could the President call forth the militia of the state to suppress the insurrection.

Id., § 2. In the legislation authorizing the Quasi-War of 1798, Congress placed limits on what President Adams could and could not do. One statute authorized him to seize vessels sailing to French ports. He acted beyond the terms of this statute by issuing an order directing American ships to capture vessels sailing to or from French ports. A naval captain followed his order by seizing a Danish ship sailing from a French port. He was sued for damages and the case came to the Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Marshall ruled for a unanimous Court that President Adams had exceeded his statutory authority. Little v. Barreme, 6 U.S. (2 Cr.) 169 (1804). The Neutrality Act of 1794 led to numerous cases before the federal courts. In one of the significant cases defining the power of Congress to restrict presidential war actions, a circuit court in 1806 reviewed the indictment of an individual who claimed that his military enterprise against Spain ‘‘was begun, prepared, and set on foot with the knowledge and approbation of the executive department of the government.’’ United States v. Smith, 27 Fed. Cas. 1192, 1229 (C.C.N.Y. 1806) (No. 16,342). The court repudiated his claim that a President could authorize military adventures that violated congressional policy. Executive officials were not at liberty to waive statutory provisions: ‘‘if a private individual, even with the knowledge and approbation of this high and preeminent officer of our government [the President], should set on foot such a military expedition, how can be expect to be exonerated from the obligation of the law?’’ The court said that the President ‘‘cannot control the statute, nor dispense with its execution, and still less can he authorize a person to do what the law forbids. If he could, it would render the execution of the laws dependent on his will and pleasure; which is a doctrine that has not been set up, and will not meet with any supporters in our government. In this particular, the law is paramount.’’ The President could not direct a citizen to conduct a war ‘‘against a nation with whom the United States are at peace.’’ Id. at 1230. The court asked: ‘‘Does [the President] possess the power of making war? That power is exclusively vested in congress. . . . it is the exclusive province of Congress to change a state of peace in a state of war. Id. f

REPORT ON RESOLUTION WAIVING REQUIREMENT OF CLAUSE 4(b) OF RULE XI WITH RESPECT TO SAME CONSIDERATION OF CERTAIN RESOLUTIONS Mr. MCINNIS, from the Committee on Rule, submitted a privilege report (Rept. No. 104–453) on the resolution (H. Res. 342) waiving a requirement of clause 4(b) of rule XI with respect to consideration of certain resolution reported from the Committee on Rules, which was referred to the House Calendar and ordered to be printed. TRIBUTE TO THE LATE HON.BARBARA JORDAN The SPEAKER pro tempore. Under the Speaker’s announced policy of May 12, 1995, the gentlewoman from Texas [Ms. JACKSON-LEE] is recognized for 60 minutes as the designee of the minority leader. Ms. JACKSON-LEE of Texas. Mr. Speaker, many fear the future, many are distrustful of their leaders, and believe that their voices are never heard. Many seek only to satisfy their private work wants and to satisfy their private interests. But this is the great danger America faces, that we will cease to be one Nation and become, instead, a collection of interest groups, city against suburb, region against region, individual against individual, each seeking to satisfy private wants. Mr. Speaker, if that happens, who then will speak for America? Who then will speak for America? What are those of us who are elected public officials supposed to do? I will tell you this, we as public servants must set an example for the rest of the Nation. It is hypocritical for the public official to admonish and exhort the people to uphold the common good if we are derelict in upholding the common good. More is required of public officials than slogans and handshakes and press releases. More is required. We must hold ourselves strictly accountable. We must provide the people with a vision of the future. Mr. Speaker, that was from Barbara Jordan, 1976, at the Democrat Convention. Mr. Speaker, last week we lost an American hero. Barbara Jordan died last week on Wednesday, January 17, 1996, a friend to many, a mentor, and an icon. The late honorable Congresswoman, Barbara Jordan, who not only represented the 18th Congressional District of Texas that I am now privileged to serve, was one of the first two African-Americans from the South to be elected to this august body since reconstruction. She was a renaissance woman, eloquent, fearless, and peerless in her pursuit of justice and equality. She exhorted all of us to strive for excellence, stand fast for justice and fairness, and yield to no one in the matter of defending this Constitution and upholding the most sacred principles of a democratic government. To Barbara Jordan, the Constitution was a very profound document, one to be upheld. The lady, Barbara Jordan, the first black woman elected to the Texas Senate, was born February 21, 1936, the daughter of Benjamin and Arlene Jordan. The youngest daughter of a Baptist minister, she lived with her two sisters in the Lyons Avenue area of Houston’s Fifth Ward. The church played an important role in her life. She joined the Good Hope Baptist Church on August 15, 1953, under the leadership of Rev. A.A. Lucas, graduating with honors from Houston’s Phyllis Wheatley High School in the Houston Independent School District

This my fellow moors is what the Bey, El, Deys, Ali’s Pasha and Al’s are legally fighting for. The reclamation of there national birthrights as moors and a nation. Yes, we ruled at that time and we will rule again. The only difference we will rule with Love.